June 30, 2010. News has reached us from various Twitter accounts and other sources on the passing yesterday of legendary graffiti artist and hip-hop musician Rammellzee.

from Gawker:

Rammellzee, the pioneering hip hop artist and Wild Style star whose ten-minute-plus 1983 record Beat Bop is still fresher than just about anything on the radio, has apparently died.

His death was first announced on the Twitter page of Fab Five Freddy, who would know; and early this morning, a post went up on Rammellzee's Myspace page reading in part "...in mourning..as i type this, i'm numb from overwhelming sadness.....The Equation The Ramm:Ell:Zee has left his physical....left his pain." Details are unclear.

from Joseph Nechvatal:

I am sorry to learn that Gothic Futurist artist Rammellzee has passed away, An official confirmation is still pending and a cause of death is not yet known. Rammellzee was an amazing artist that I knew back in the early 80s. Check him out on Tellus Audio Cassette Magazine - a live radio program hosted by Isaac Jackson on WBAI-FM September 20, 1982. Edited by Joseph Nechvatal. Tellus link.

from Wikipedia:

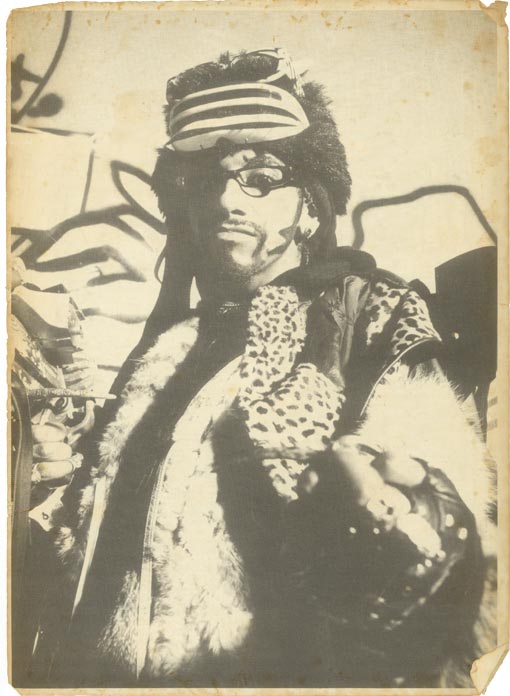

Rammellzee (or RAMMΣLLZΣΣ, pronounced "Ram: Ell: Zee", born 1960 in Far Rockaway, Queens, New York), was a graffiti writer, performance artist, rap/hip-hop musician and sculptor from New York. His death was announced on 29th June 2010.

Rammellzee's graffiti and art work are based on his theory of Gothic Futurism, which describes the battle between letters and their symbolic warfare against any standardizations enforced by the rules of the alphabet; his treatise, "Iconic Panzerisms", details an anarchic plan by which to revise the role and deployment of language in society. Rammellzee is often identified as an artist apart of the Afrofuturism canon; Afrofuturism is identified discourse concerned with revisioning racial identity through the tropes of science fiction and fantasy narrative or aesthetics.

He was also instrumental as one of the original hip hop artists from the New York area who introduced specific vocal styles which date back to the early 1980s. His influence can still be heard in contemporary artists such as The Beastie Boys and Cypress Hill. His song "Beat Bop" was featured in the film Style Wars.

Discovered by a larger audience through the 1982 cult movie Wild Style by Charlie Ahearn, his fame in graffiti circles was established when he painted New York subway trains with Dondi, OU3, and Ink 76, and doctor Revolt. Rammellzee was also a member of the Death Comet Crew, with Stewart Albright and Michael Diekmann. In 1988, he and his band Gettovetts recorded the album "Missionaries Moving."

Rammellzee's website: http://www.gothicfuturism.com/

Greg Tate's interview from WIRE #242, April 2004:

Rammellzee: The Ikonoklast Samurai

http://www.thewire.co.uk/articles/4501/

other sources:

http://www.magical-secrets.com/artists/rammellzee

http://www.thedailyswarm.com/headlines/rip-rammellzee/

Rammellzee on Ikonoklast Panzerism (video excerpt from an interview in a skate shop):

Ramellzee, Toxic C1, and J-M Basquiat @ LA's Rhythm Lounge, 1983

Rammellzee's passing in the NY Times

From the NY Times Artsbeat blog. A full obituary will appear at a later date.