Artivists and Mobile Phones: The Transborder Immigrant Project

November 17, 2007

CorinneRamey

http://mobileactive.org/artivists-and-mobile-pho

Ricardo Dominguez calls himself an "artivist." Half political activism and half art, Ricardo's projects blur the boundaries between the aesthetic and the political. "We always view our activism within the frame of art and the poetic," said Ricardo. Ricardo was part of a team that was recently awarded the Transnational Communities Award for a Transborder Immigrant Tool that uses GPS-enabled mobile phones to help immigrants crossing the border between Mexico and the United States.

MobileActive recently had a discussion with Ricardo on art, activism, and mobile phones. Ricardo, a researcher in the Calit2 lab at the University of California at San Diego, was given the award along with colleagues Brett Stalbaum, Micha Cárdenas y Jason Najarro. The project seeks to create a way for immigrants to orient themselves while crossing the border between the United States and Mexico, which is traversed by thousands of immigrants each year. The device seeks to reduce the number of deaths along the border by helping immigrants locate resources such as water caches and safety beacons.

The idea for the project arose from a program called the Virtual Hiker, a project of UCSD visual art professor Brett Stalbaum. "Brett gets lost even going to his house," joked Ricardo, "so he started working on a locative media project called the Virtual Hiker...He developed an algorithm that took into account a certain terrain, and created a virtual trial or hike based on those algorithms." By using GPS, the program created virtual hikes and would orient the user towards certain landmarks. Brett was able access "the kind of utility cloud that GPS offers," said Ricardo.

The Virtual Hiker program led the team to question ways that GPS technology could be used to help immigrants crossing the border. "We asked ourselves, what were the spaces of necessity or danger on the border, and how could we plug in this new element of the GPS structured cell phone?" said Ricardo. The answer to that question was the Transborder Immigrant Tool.

The tool is built on a Motorola i455 phone, which offers several advantages. Not only is the phone cheap -- about $40, according to Ricardo -- but no service is required for GPS functionality. "What we needed was a really inexpensive telephone, one that we could crack the GPS system, and one that would accept new algorithms."

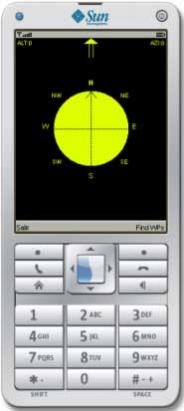

The team took language into account when designing the application. "We needed to design the interface in a way that would be somewhat universal in terms of the community that would be crossing the border," he said. Many of the migrants are from indigenous communities, and wouldn't necessarily speak Spanish. The end result was a navigation system that looks like a compass. The phone also vibrates in response to certain landmarks, like water or a highway. The vibrations allow the user to concentrate on the surrounding environment instead of constantly looking at the screen of the phone.

Ricardo sees even the interface of the phone as having artistic value. "We were trying to think of many layers of communication -- iconic, sound, vibratory," he said. Additionally, the program helps the user not only avoid getting lost, but helps him or her find a more aesthetic route. "The algorithm would look at it not just in terms of a map or a politics but by suggesting the most aesthetic crossing," he said. Eventually, the people using the tool to cross the border would form an imaginary "mass desert painting" or "walking art," Ricardo said. "All the immigrants that would participate would in a sense participate in a large landscape of aesthetic vision."

The project is still in its preliminary stages, but by the end of next year the team hopes that it will be a working and usable tool. "In the next stage, the research team will go to both ends of the border and work with the tools directly in terms of triangulating the info to the satellites," said Ricardo. The final step of the project will include workshops and trainings with groups that work with immigrants who are getting ready to cross the border. Possible partners include Casa Imigrante and the Centro de Informacion para Trabajadoras y Trabajadores (CITTAC). "We hope to get them to communities that interface with people getting ready to cross," said Ricardo.

Ricardo says that the team currently has enough funding to pay for 500 phones, and hopes to purchase more in the future. He also mentioned the possibility of adding about $50 of phone time to each tool, although, he said, that team recommended only using the tools as phones in emergencies for security reasons. The team is also working with a group of teachers to design a simple pamphlet with instructions on how to use and upgrade the tool. He hopes the instructions will be similar to the safety cards available on airplanes -- they'll rely more on pictures and icons than language.

Ricardo sees the Transborder Immigrant Tool as part of a larger trend of border disturbance art. "There's a long history of artists at the border creating gestures that question the very nature of the border," said Ricardo. Because disturbance art is framed as art, and not as solely political activism, the "artivists" are given more leeway politically. "The reason they can't stop us is that we always frame all these gestures within the poetic frame." By framing politics as art, and art as inextricably linked to politics, projects like the Transborder Immigrant Tool are able to survive as both a life-saving device and an "artivist" concept.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| compass15.png | 74.65 KB |