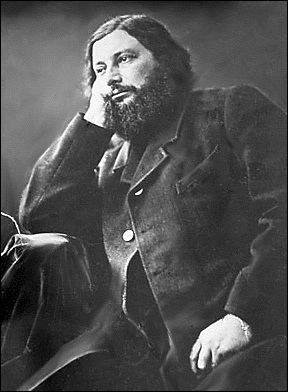

Gustave Courbet (portrait by Nadar; public domain)

Gustave Courbet (portrait by Nadar; public domain)

While I don't reblog as a rule, I cannot resist this blast from Paul Werner on the MMA's Courbet show. Paul is my favorite firebrand art historian. In this basic history lesson, he reminds us that Courbet is significant not only as a painter, but as a leading cultural revolutionary. Courbet's texts lead off the splendid new "Art and Social Change" reader from the Tate, edited by Will Bradley and Charles Esche. Allan Antliff opens his new book "Anarchy and Art" (AK Press) with a chapter on Courbet and the Paris Commune of 1871 entitled "A Beautiful Dream."

This insistence on recalling the artist as administrator is not new. In the early 1970s, as the Art Workers Coalition was storming in New York, Linda Nochlin published an essay ``Museums and Radicals: A History of Emergencies'' in Brian O’Doherty's anthology which again details Courbet's role in the Commune, protecting art from the government. A century later Courbet's heirs were on the steps of the Met. Carl Andre swept them with a broom. Little wonder this is a chapter in the legacy of the French painter which the American museum would choose to, um, downplay.

WOID XVIII-44. Review: Bonjour, Comrade Courbet! [I]

Gustave Courbet

Metropolitan Museum of Art

http://metmuseum.org

Through May 18

Courbet was a "Republican?" Golly, geez, it must be true because the New York Times just said so. Courbet, the great French nineteenth-century painter and political activist, the man who sold to the ruling class and yet refused to sell out, the man who was almost shot for his participation in the Paris Commune, would have voted for John McCain according to Roberta Smith, the Times' art critic.

Well, the Times never lies. Well, not exactly. Late in 1851 when a Parisian journal denounced Courbet as a "socialist painter," Courbet responded:

"I am strong enough to act alone ... Monsieur Garcin calls me the socialist painter; I gladly accept that description; I am not only a socialist, but also a democrat and republican, in short a supporter of all that the revolution stands for, and first and foremost I am a realist."

Back then a "republican" (as opposed to a "Republican" nowadays), meant somebody who supported the Second Republic, the democratic government that had been brought to power by the working class in the Revolution of 1848. Whatever Courbet's words might have meant in 1851, they took on another meeting two weeks later when the Republic was brought down by Napoleon III. After that, anyone who thought of himself as a Republican (like Courbet's friend Manet) would be simply placing himself among the enemies of the Regime.

Courbet, unlike Manet, didn't keep his head down. Armed with the prestige he'd earned under the Republic (notably the medal that allowed him to show his paintings in the State-sponsored "Salon" without a jury's approval), Courbet embarked on an eighteen-year career of painterly and political resistance, with considerable help from his friends and fellow-troublemakers: the second lie from the Times (the more egregious one), is the description of Courbet as a "narcissistic loner." Narcissistic, maybe, but Courbet had plenty of friends, just not the Times' kind of people.

Among them was the Anarchist legend Pierre-Paul Proudhon - there's a painting of him in the show. Of course, say the art historians, that means Courbet can't have been a "real" activist since Marx himself dismissed Proudhon in The Poverty of Philosophy. This didn't stop Courbet, or Proudhon's followers, from joining the Paris Commune of 1871: Courbet himself was elected to the governing body of the Commune and served on its committee on public education, as well as working to reorganize the museums, art schools and exhibitions on democratic lines, which kind of conflicts with Wikipedia's assertion that he saved the museums from "looting mobs." Oh, well.

Unless they mean the looting mobs of right-wing troops that stormed Paris, shooting some 30,000 men, women and children and shipping thousands more to the colonies. Courbet was captured, imprisoned, and eventually charged with destroying the hideous Vendôme Column, for which he was fined an enormous sum. Courbet fled to Switzerland where, for once, he might have been described as being a loner, except he seems to have had plenty of friends helping him churn out those chocolate-box paintings that bear his signature. A troublemaker to the end, he died on December 31, 1877 - or maybe January 1, 1878. Nobody knows. Not even the New York Times. Especially not the New York Times.

[part one of a two-part article]

- Paul Werner

http://theorangepress.com

WOID: a journal of visual language

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Gustave_Courbet.png | 38.4 KB |