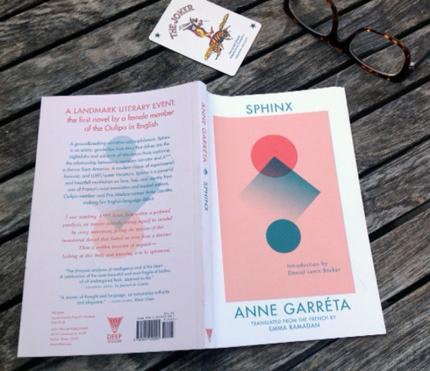

Book Review:

Anne Garréta’s novel Sphinx

Published by Deep Vellum Publishing, 2015

Translated by Emma Ramadan

My recommended summer reading is the critically acclaimed thin novel Sphinx by Anne Garréta – originally published in French by Grasset in 1986 when the author was 23. This year, it has been eloquently translated into English by Emma Ramadan with support from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the United States. Published as a simple affordable paperback or ebook by Deep Vellum Publishing (a Dallas-based not-for-profit literary arts organization), it tells, in sometimes ravishingly beautiful (if ornamental) language, of an odd sort of love relationship set mostly in seedy 1980s night time Paris. An, at first, cerebrally-intensive affair plays out between the genderless/nameless 22 year old narrator (a lapsing theology student and newbie chichi club DJ) and A***, a 32 year old, genderless, black New Yorker and erotic dancer working a trashy-sex club on the left bank. With such sentence fragments as “… I moved through the smooth insides of a whirlwind and gazed at deformed images of ecstatic bodies in the slow, hoarse death rattle of tortured flesh,” its genderless cadence speaks to the broad poetics of love and its powers of latent liberation in almost apocalyptic fashion, so fashionable in the 80s. At times I was delightfully reminded of Jean Genet’s great masterpiece of excess: Our Lady of the Flowers.

Sphinx is a pleasingly transgendered work of art in terms of its malleability. The two lovers (the narrator and the narrator’s love interest) give no indications of grammatical gender when in dialogue. There are, however, possible (possibly misleading) hints I detected, such as offers of cigars to the narrator and some crude macho verbiage used.

All of the minor characters in the book are fully embodied/gendered (if unnamed) such as Padre***, a rather scandalous priest who introduces the narrator to club night life and then assists in a coverup of a drug overdose that offers the narrator her/his prime DJing gig at club Aprocryphe (as described, sounds like Les Bains Douches). Alternately reading A*** as either Adam or Amie supplies the story with added levels of intrigue. Even more so as the intimacy of the affair begins largely a-sexually. This “love” is somewhat of a mystery at first, as the two characters share no common intellectual or aesthetic interests or passions. The sole engine of narrative development is the brainy white narrator’s carnal passion for A***’s stupendous black body; the product of a mixed race American family. A desire/vision so strong that the narrator once describes it (oddly) as seeing through a “veil of blood.”

Involved in theological speculation, the narrator naturally intertwines internal-monologue references of sexiness with Godliness – and that brought to mind certain extravagant Prince songs from the 80s, like Controversy. Also the book’s descriptions are typical of the hothouse style of some of the best 80s books, recalling for me Anaïs Nin’s A Literate Passion: Letters of Anaïs Nin & Henry Miller, Gary Indiana’s White Trash Boulevard and Patrick McGrath’s The Grotesque. But Sphinx, at times, uses a syntax so rich and evocative as to border on logorrhea. A style so purple as to spill over into ultraviolet.

Besides this bruised desire, a few other aspects of difference/attraction between the narrator and the narrator’s love interest are explored fleetingly, such as those between A***’s American-in-Paris exuberance and the narrator’s generally refined/restrained French sophistication/ennui. Midway into the book, there is a strongly disjointed scene between the two friends where the giddy narrator is keen on declaring love and repressed sexual desire for A*** at the Café de Flore. These strong emotions are met with rebuke.

There was an added level of confusion in this scene. At first the narrator proclaims distain for the intelligencia that gather at the Flore (stating that he/she has never stepped foot into the place) and on the following page takes a table there where she/he “always insists on sitting.” A strange and unnecessarily confusing mixed message, I would say, in already muddy waters.

Hopes of jelling such desires are intended on a trip the friends make to Munich, where the narrator tours church architecture in search of metaphysical and artistic wonders (and eventual sexual gratification won through imaginative perseverance) with a visit with A*** to Saint***. The description of Saint*** suggests that it is (thinly veiled) the 18th century church Saint Johann Nepomuk, better known as Asamkirche (Asam Church) after its architect Egid Quirin Asam. Together with his brother, the painter and architect Cosmas Damian Asam, they created a masterpiece of sumptuous Rococo there where on entering the vestibule of the church, one encounters a consummate example of Bavarian excess. In this hybrid space, painting, sculpture and architecture work together in fabricating something between a prodigal odium, a playhouse, and an angelic quixotic grotto.

Saint*** plays a pivotal role in explaining the continuation of their unrewarding asexual love relationship by emphasizing genderless angelic bodies in relationship to space, weight, and light. After visiting Saint***, sharing a bed, the lovers “love” each other, but do not touch. As such they remain bound up with the principles of otherness and mutability typical of angelic spectral theology where angels are thought to be carriers of messaged sentiments. In that the feelings/messages delivered are airborne and move, angels fly and are winged, implying that they have virtus (inherent power and potential). Thus, since the lovers contain the principles of virtual mutability, they posses a quasi-material body that cannot be circumscribed by place or endowed with position.

The genderless lover-angels I discovered midway in Sphinx seem constructed from the quantum nature of light. They are hyper-sensitive semi-material lovers, fabricated of semi-transparent matter. They hover above distinctions. This intuition on my part was confirmed when the lovers, back in Paris, tipsily dancing, achieve a state of “lightness of being.” That exalted state leads them to the long awaited consummation of their affair where the “temporal order of events, even the simple spatial points of reference” blurred and disappeared when their “crotches crossed.”

Hence, these lovers appear as paradigmatic representations of the out-of-bodiness of virtual substance characteristic of spirituality (ignudo spirto). That image of fleshy distentio seems, to me (albeit symbolically), to be the main point of Sphinx. The idealization of the lovers genderless flesh and their side-by-side spatial location on the bed, provide them with possession of the virtual. These winsome figures’ semi-transparent relationship to each other conceptually carries over from Asamkirche’s richly architecturally domed space from which angelic figures emerge and return towards the light-filled circular opening. A rounded light which constantly re-defines them with every fluctuation in its intensity. A garland of angels is transposed there into relief sculptures which overflow the frame and expand as if they were released from materiality on route to, and from the intricate dome which dominates the composition and which both physically clarifies and luminescently dissolves their form.

The title Sphinx, comes from an English language song that the narrator, prior to a trip to New York, hears and fixates on while watching A*** dance on stage in a club. I suppose the author, Anne F. Garréta, drew this audio image from the disco era song written by Amanda Lear with music by Anthony Monn (who produced the track). The Sphinx was released as the first single from Amanda Lear’s album Never Trust a Pretty Face. During the 1960s, Amanda Lear was companion to Salvador Dalí who told her to pretend to be man, and she played with that perception throughout her career. It had been said that Lear worked transvestite revues in Paris (like Madame Arthur and Le Carrousel) much like those described in the novel. Lear was untruly rumored to be transsexual and even a hermaphrodite Sphinx, the book, makes use of this little known connective material so as to bake into its genderlessness theme an inverse proposition that gestures at genderfullness.

This implied mid-book angelic fullness is pretty much that apex of the love story, as the lovers, now living together in Paris, start to drift apart. The narrator prefers reading Gustave Flaubert and looking at the Renaissance paintings of Andrea Mantegna, while A*** prefers shopping and low-brow TV shows. This slow drift apart is finalized with a tragic break: that I won’t spoil for you here by recounting. I can say that A***’s image, in the eye of the narrator, enters a “virtual space” that “swallowed up” the gaze of the narrator. Following this break, the narrator turns sad, inward and taciturn, returning to academic theology; mining the negative depths of Apophatic speculation. There are long pensive sections here punctuated with drastic and flamboyant descriptions of two further demises. One marked by an almost angelic act of ephemeral and quixotic compassion and charity – the other by stupid brutality. Neither of which washes away the shimmering virtual depths of intelligent tenderness one lives with when reading this book.

One caveat: Save for last the interesting Introduction by Daniel Levin Becker that situates Garréta’s work within the tradition of experimental Oulipo formal constraints. Following the success of Sphinx in France, Garréta was invited in 2000 to join the prestigious Oulipo group due to this book’s inventive use of gender neutrality. In French, nouns are gendered, and consequently the sex binary pervades subject-verb agreement. Garréta navigated her way around this binary with admiral delicacy and her English translator Emma Ramadan has paralleled the feat. But you don’t read Sphinx for the word games. You read it for the painterly imagery, lush language and passionate inquiry into the virtual aspects of desire, need and sexual passion.