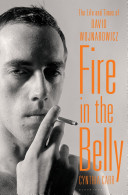

Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz by Cynthia Carr

Illustrated Hardcover, 624 pages

Published by Bloomsbury USA

ISBN 1596915331 (ISBN13: 9781596915336)

$35

******

This will not be an adequately objective book review of Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz by the clear-eyed Cynthia Carr (many correct praiseworthy reviews already exist of this plainly excellent but devastating book) but more of a series of subjective/personal reflections mixed with my critical reactions to Wojnarowicz’s art (then and now) more appropriate to a blog.

Marvin Taylor at the Library and Special Collections at N.Y.U. first pointed me at Carr’s book on David Wojnarowicz (who died a harrowing death of AIDS at the early age of 37 after an impressive stretch in AIDS activism and in the defense of freedom of expression) and I thank Marvin for it. It is a passionate portrait of David as well as the now mythic East Village between the late 1970s and late 1980s, then a sanctuary for diehard artists and galleries. A period that soon was followed by the neighborhood’s gentrification, along with its art community’s devastation by HIV/AIDS and the national culture wars of the 1990s. I read it, at times, through teary eyes.

Fire in the Belly is satisfactorily illustrated with color and black and white plates of Wojnarowicz’s art and snapshots of artist friends and other people in his emotionally messy life (many of whom I knew nothing of, but there are others that I knew rather well from that period). It is both a delight and a fright to revisit those days with some of them.

By chance I finished reading David’s mostly sad story (it’s sad to read about his relationships falling apart due to his insecurities, paranoia and abusive rage) on the happy day that Barak Obama won re-election for president. Obama's late-term embrace of same-sex marriage seems to have resulted only in political benefit with no political impairment. Tammy Baldwin in Wisconsin became the first openly gay person elected to the Senate. New laws to legalize both same-sex marriage and marijuana consumption were enacted in multiple states with little controversy. In short, progressive social liberalism was triumphant and crippled America's far right wing. All of this was unthinkable in the days of David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992).

Accordingly, I will try to think through what is the relevance of David’s art and activist work in a New York City (indeed in an America) that has now largely vanished.

***

Fist some background from my (admittedly specific) point of view.

I encountered David’s long face and deep voice for  the first time in May 1983 at the Speed Trials noise rock concert series organized by Live Skull members at White Columns. David and I did the art on the walls for the Speed Trials as an anonymous space share. It was not a collaboration. Within it, various performance artists, such as Ilona Granet, intermixed with the music of The Fall, Beastie Boys, Live Skull, Sonic Youth, Lydia Lunch, Elliott Sharp, Swans and Arto Lindsay.

the first time in May 1983 at the Speed Trials noise rock concert series organized by Live Skull members at White Columns. David and I did the art on the walls for the Speed Trials as an anonymous space share. It was not a collaboration. Within it, various performance artists, such as Ilona Granet, intermixed with the music of The Fall, Beastie Boys, Live Skull, Sonic Youth, Lydia Lunch, Elliott Sharp, Swans and Arto Lindsay.

It had been a pleasant experience working next to him and I remember him from that day as being gentle and pleasant. I had seen David in an exhilarating performance with the noise band 3 Teens Kill 4 at the Pyramid Club, but David had recently left 3 Teens Kill 4. As we walked back from far west Spring Street to the Lower East Side together after completing the installation, we talked about our favorite bookstores and books, about our passion for Arthur Rimbaud and French Symbolist poetry, about the growing nuclear war threat in relation to his stencil street work of the burning building and my nuclear war street posters. Also we spoke about his dumping of a pile of cow bones on the stairs outside of the Leo Castelli Gallery (of that I did not approve). He did not impress me as someone particularly angry - or for that matter as someone into anonymous sex (he exhibited no gay clone clichés, no gay cruising come-ons) - and I was surprised to learn otherwise on both accounts in the book.

However, we did not become friends and I did not know him in any profound way whatsoever. He did not participate in the conceptually bent Gallery Nature Morte scene, or the more “political” Colab / ABC No Rio circles that I was active in at the time. Nor did I see him in the Brooke Alexander Soho Gallery setting. But I would see him now and again and say hello at East Village openings or nightclubs.

We next appeared together in the Tellus Audio Magazine #5-6 - Special Audio Visual Issue (that I co-edited). His admirable noise piece for that issue was a collaboration with Doug Bressler called American Dreamtime, now archived at Ubuweb at http://www.ubu.com/sound/wojnarowicz.html

The next time we spoke was in 1985 at the studio of Timothy Greenfield-Sanders when Timothy photographed us, together with other East Village artists, for "The New Irascibles," cover of Arts Magazine (reproduced in the book on page 283). David was not very cordial that day, as I recall. Yet he seemed still tender to me.

Perhaps some aspects of David’s life and work need not to be romanticized. Years later in 1989 he would rage against me for not including his collaborative work on sex and AIDS with Marion Scemama in my show Erotic America at Galerie Antoine Candau in Paris (catalogue essay by Eleanor Heartney), comparing me to Hitler (page 410). Such is the insufficiency of crowning him with the militant hero persona.

My intention for the show was to address the AIDS epidemic with a counter-attack of ecstatic Eros. But perhaps something positive came from David and Marion’s disproval of my choice of not including their work in the show (it was attacked via Marion for ignoring HIV/AIDS in Liberation, the leftist Parisian newspaper, while at the same time being censured by the local police). Carr states that this event “inspired” David to speak out on HIV/AIDS even more explicitly in his work and activism. This is important to me as Wojnarowicz’s gay activism is the most important thing I think to cherish about him as preserved in his many writings and art works dealing with AIDS (certainly not the lousy and nasty death trip stuff he foolishly fooled around with).

It is quite possible that this event nudged me closer to my HIV/AIDS themed computer virus project that began in 1991 (ongoing). I usually attribute the birth of the computer virus project however to my direct experience with, and exposure to, the deadly virus through my relationship to the tormenting AIDS death of Bebe Smith. That and the AIDS death I witnessed of my friend and neighbor the performer Tron Von Hollywood (hear http://ubumexico.centro.org.mx/sound/tellus_1/Tellus-1_15_Tron_Von_Holly...). That period cracked open an emotional range in me between dread for one’s life and happy memories of a fading wild sexual freedom.

Regardless, I had little idea of David’s terrible AIDS background at the time. Not until I read Cynthia Carr book did I fully understand. Nor did I know that he had had a harrowing childhood of emotional and physical abusive at the hands of an alcoholic father and distant - soon divorced - mother, or that he was at one time a young gay hustler. On this last point however, Carr points out that even as she was exhaustive about verifying facts about his childhood and his years as a hustler, Wojnarowicz sometimes exaggerated his hustling, for effect. Still I read the book with generous eyes.

Equally, I knew nothing of the years Wojnarowicz spent working on poetry before he became an artist. Indeed Carr does a remarkable job cataloging David’s early poetic publications and readings. I was well aware of his key relationship to the photographer Peter Hujar, his mentor, but not at all with his longer, if punctuated, relationships with Jean-Pierre Delage and then Tom Rauffenbart. Or his hard drug use (indeed it seems to me that David took the wrong drugs while reading the right books (Jean Genet)). Nor did I know of his times spent in Paris.

***

Now my aesthetic problems with David’s work

David’s surrealistic imagery is way too blunt for me. In reading this book I kept waiting for a struggle with style that never came. His work offers little in stylistic innovation, as it depends on a pretty standard, sub-surreal, technique of collage.

1987.jpg)

Worse, this collage language of deliriousness poetic free association seemed to have opened up too many superficial associations for him and to have closed down his emotional capacity to connect. So his work exudes a mood of sullen dissatisfaction that does not appear helpful in today’s world. He discovered through French symbolist poetry the freedom of re-aligning thoughts and images, but he never went further in questioning the adequacy of standard representations. He never found the magical capacity of establishing new visual logics through the consolation of patterns. Indeed the pattern of his life was stuttered with violent ruptures and anonymous intimacy. He lacks continuousness.

He has been compared to Arthur Rimbaud, but his poetry and writing style is unsophisticated. Even his straight up rants cannot compare to those of Antonin Artaud.

His work rarely winked or smiled, and I think it was that heavy earnestness about it that repelled me then and now. His compositions are stogy, almost Pre-Columbian in arrangement, and that restricts the heart from joyful leaps.

Indeed, his is a mood of one who has embraced ugliness as a state of spiritual disgust. Some of the work is revolting, in the positive sense of the term.

And he is too Romantic in the idealized sense. Worse, David standardizes and stereotypes in his work. Wojnarowicz most famous work was his short silent film "Fire in the Belly," which elicited controversy because of an 11-second sequence that featured ants crawling over a crucifix. This is actually pretty tame and corny stuff when compared to some mesmerizing films of Luis Buñuel (L'Age d'Or, for example).

Many of Wojnarowicz’s paintings are too hectic, packed as they are with iconography: animal skulls, flowers, gears, locomotives, houses on fire, sleeping men, threatening soldiers, and more and more and more. And, oh please, Jesus with a heroin syringe in his arm (considered blasphemous by some). Where are the fresh ideas?

His stated goal was to penetrate life so as to recover what he called the “pre-invented world,” - the invented world being what most of us would recognize to be Jean Baudrillard’s simulacrum. It seems he was struggling in his art for a de-simulation that attempts to re-establish a private critical distance achieved through the challenge of (and disparity between) pleasure and frustration. (1) But for me, David never achieved de-simulation in his work (in any of it, and certainly not in his noise work with 3 Teens Kill 4). Nor a state of free flowing virtuosity, as did Jean Genet in his writing or as Rhys Chatham did in his post-punk guitar music. I think that perhaps David tried to do too many things: after all, he was a writer, painter, photographer, noise musician, filmmaker, and a performance artist. And so he was at times only sufficient where he might have soared if he had been committed to a craft. For example his 1985 foray into the Cinema of Transgression with the 28minute film Where Evil Dwells (with Tommy Turner) then as now appears merely juvenile.

Also his writing style never developed. And even as his work is rightly heralded in gay history and queer cultural criticism for its fearlessness, it does not open an insightful window for me into gay imagination the way Pierre Molinier does. It never came through looking at his work, or reading his texts, or even reading this first-rate book. I could not understand his deepest cravings. Clearly he was not in search of fame or deep love, not social acceptance or grace, and not, apparently, even sexual fulfillment. The closest I came to understanding him is through his ranting and raging coupled with continuous cold spontaneous anonymous sexual encounters of the kind I now associate in the straight world with the angry gibberings of Rush Limbaugh and the dégoûtant exploits of Catherine Millet (see, no don’t, her book The Sexual Life of Catherine M) and/or more tragically the recent sex life of Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Perhaps David’s most secret desire was to be a porn star in his own private Idaho.

Now I will consider David’s work in light of the 2012 presidential election and the new America it has illuminated: a highly diverse and broadly progressive America. A 21st-century America: multiracial, multi-ethnic, global in outlook and moving beyond centuries of racial, sexual, marital and religious tradition, perfect in the way that Obama perfectly personifies this state of varied mutability. The craziness of David’s America, with its violently apocalyptic coloration, is a world I think that no longer is applicable to progressives, but rather typifies the raging, dying far right. (We are physically outgrowing divisions between “us” and “them.”) Moderately liberal multicultural youth around the world, I think, are unable, unwilling and uninterested in indulging in such us/them concepts and tactics. I don’t think they even see them outside of class differences.

I agree that the importance of David’s work rests not just in the place it will take in gay history and queer cultural criticism but in the place it should take in American history and the larger, general discipline of art history. So I think that the aggressive warring craziness of 1980s America we see in David’s work is happily now irrelevant. There are no buried complex themes in his work that I can find relevant to today. David’s cold spontaneous anonymous self-centered world is gone. As I suggest above, it had, bizarrely, become the domain of the raging aggressive, abusive and paranoid world of the far right, but that world is in the process of disintegration. This is basically the problem I had then (and have now) with neo-expressionism’s valuation of the artist ego.

So read this book, but as a cautionary tale. There are some heroes here: all the people, including the author Cynthia Carr, that looked after David during his demise, and clearly Barry Blinderman acted heroically in his support of David’s work, but David himself? I don’t see it. Yet, he has done more than enough and must be valued and remembered for it, even as we move forward together. But look to un-angry alternatives, like the idea of the commons. Anger has its limitations in the long run. Forward then.

**********

(1) For a lot more on this and my theory of counter-simulacrum see my essay Jean Baudrillard and a Counter-Mannerist Art of Latent Excess in my book Towards an Immersive Intelligence: Essays on the Work of Art in the Age of Computer Technology and Virtual Reality 1993-2006 New York, NY: Edgewise Press. 2009 or online here at http://www.ubishops.ca/baudrillardstudies/vol3_2/nechvatal.htm

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| David Wojnarowicz, Water 1987.jpg | 112.91 KB |

| irascibles-80s-big.jpg | 114.94 KB |

| David Wojnarowicz 1982 Untitled (Green Head).jpg | 80.03 KB |

| 83may04-speedtrials.jpg | 42.58 KB |

| David Wojnarowicz, Wind (for Peter Hujar) 1987.jpg | 113.2 KB |