Families standing in the flooded Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, holding photos of their disappeared, 1983. Photo by Daniel García.

Perder la forma humana. Una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina // (Losing the human form. A seismic image of the eighties in Latin America) Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid

October 26, 2012 - March 11, 2013

Introduction – This is a major exhibition of political art. It is probably the best I have ever seen. “Perder la Forma Humana” presents the situations and the creative responses to the epoch of dictatorships in Latin America in the 1980s. The presidency of plastic hero Ronald Reagan was a disaster for our neighbors to the south if they professed any opposition to the smooth workings of multinational capital. Activists, most of them young, were detained, tortured and killed by the tens of thousands during many long years of harsh rule by right-wing generals. The U.S. military helped to coordinate these repressions. (This kind of federal coordination was recently echoed in the nationwide shutdown, benign by comparison, of the encampments of the U.S. Occcupy movement.)

At the time, U.S. activists knew of this terror. Occasional demonstrations were held throughout the 1970s. Indignation really flared in 1984 with the massive campaign of state terror in El Salvador, conducted by military directly trained in the U.S. (at the notorious School of the Americas, later renamed).

With the Artists Call Against U.S. Repression in Central America, the U.S. artworld at last moved to condemn this ongoing horror with a national campaign of coordinated exhibitions. What effect did that have? Who knows? At least our consciences were salved. Now, is it merely this regret at earlier half-heartedness that leads me to so strongly declare for this show? Is it merely guilt at the lame gestures of solidarity which failed even to bring the mass murders to public attention 30 years ago?

No. This show is really great. And Cildo Mireiles isn't even in it.

I have nothing against the Brazilian art star who is very well known in the U.S. for his subtle politicized conceptual art series “Insertions Into Ideological Circuits.” This may have been all that was possible in the 1970s Brazil of the generals. But “Perder” isn't at all genteel or subrosa. Nor does this work make any accomodation to mainstream art market aesthetics. “Perder” spotlights actions, not artworks and collectives, not authors. In doing this it is an exemplary pedagogical exhibition of the cultural history of a very dark time.

This is a testament to the important work of the curatorial teams of the MNCARS. It is a team that extends far behind the walls of the institution. This show is a product of the Red Conceptualismos del Sur (RedCSur; conceptualisms of the south network),* an extraordinary assemblage of curators, critics, artists and poets who have been working for years to uncover precisely these buried histories so crucial to an informed understanding of the operations of creative people under conditions of great political repression.

What they have come up with – the exhibition at least – since I have yet to see the catalogue – is satisfying in every respect. I emphasize this because the normal white cube and art market hangups that cling to nearly all U.S. curations are bracingly absent in this show. Here we really are out of the swamps and fogs, standing in the light and on high ground.

Given my low level of Spanish – the show makes little concession to those who don't speak it – I can't easily explicate this work. So, in order to post at least before the show closes, I reproduce the English wall texts of the exhibition below. Actually, that's plenty.

* See http://www.museoreinasofia.es/redes/presentacion/conceptualismos-del-sur... for texts; and http://conceptual.inexistente.net/ for bios and contacts.

///////////////////////////////

The following texts are those used on the walls of the exhibition, as provided by the press department:

AREA A

LOSING THE HUMAN FORM

The image of mutation that inspires this exhibition’s title invokes a turn of phrase from the Argentinean musician Indio Solari, addressing two dimensions of the materials gathered here. It alludes, first of all, to massacre and extermination, to the crushing effects of violence perpetrated by military dictatorships, the suspension of civil liberties, and revolutionary guerrillas. Secondly, it refers to the metamorphosis of bodies and the experiences of freedom that occurred at the same time—as forms of resistance or subversion—during the 1980s in Latin America.

Gianni Mestichelli with the Compañía Argentina de Mimos, early 1980s.

The exhibition presents a partial cartography that reveals the multiple and simultaneous appearance, in different contexts, of modes of action that expanded the cultural and political vocabulary. To this end, they relied on precarious or ephemeral media and genres such as screen prints, performance, video, poetic action, experimental theatre, and participatory architecture. Very disparate episodes are brought together here—ranging from images recorded by critical photojournalists during the military dictatorships in Chile and Argentina to the survival of the Arete Guasu ritual among the members of an indigenous community in Paraguay; from acts of sexual subversion and performances in spaces on society’s margins in countries like Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Perú, Colombia, Cuba and Mexico, to the creative strategies deployed by human rights movements in the Southern Cone.

Losing the Human Form is the result of an ongoing research project of the Red Conceptualismos del Sur (the “Conceptualisms of the South” Network). This vast collection of works and documents addresses the current historical crossroads, from the light and shadows that the palpable memory of those experiences casts on the present.

AREA B

DOING POLITICS WITH NOTHING

The artistic activism of the 1980s was marked by the defeat of liberation movements in various Latin American countries and by its resistance to dictatorships. This fact differentiates this period from earlier years, when strategies of artistic action aspired to participate in revolutionary and emancipatory processes. In the eighties, in contrast (and with the exception of Perú), art lacked any prophetic or idealistic dimension. Rather, it was born of defeat. It was an art that had been disarmed.

This activism developed in a space that was distinct from that of museums, galleries and artistic institutions: the space of social movements. Aesthetic action became a political praxis whose objective was, in many cases, to render visible all that had been erased both by the dictatorships and by the pacts that ushered in democratic transitions.

The modes of production and distribution of these actions were precarious, if not marginal: their graphic supports were screen prints, photography and the body itself. In this sense, a constant practice is the subversion of advertisements and the development of a “popular” political graphics.

The effects of some of these actions radiated outward among the social body to the extent that their artistic origin was forgotten. Others failed in their political objectives but still functioned as constructs in the collective memory.

AREA C

TERRITORIES OF VIOLENCE

Various authoritarian governments imposed repressive policies when confronted with the progress of popular insurgencies, coordinating a secret network among the military dictatorships of Paraguay (1954–89), Brazil (1964–85), Bolivia (1971–82), Chile (1973–90), Uruguay (1973–85) and Argentina (1976–83). It is estimated that more than 400,000 Latin Americans were assassinated as a result of political violence. At the same time, in the context of ostensible democracies like Mexico or Colombia, the appearance of mutilated bodies provided the quotidian face of terror.

In response to oppression, various forms of resistance and civil disobedience emerged—both peaceful and violent, and ranging from street clashes to organised guerrilla actions. A particularly prominent case is that of the Maoist Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), who in 1980 declared a war of the people against the Peruvian state, giving rise to a bloody armed conflict in which acts of repression were perpetrated by both sides, leaving in their wake nearly 70,000 victims, the majority of whom were peasants.

In these “territories of violence,” people were subjected to genocide, torture, kidnapping and forced disappearances. As the eighties progressed, mass graves and concentration camps came to light, and the process of exhuming of those bodies revealed tens of thousands bearing the signs of torture—the victims of assassination who were buried clandestinely. Thus, a new iconography of terror emerged in the mass media, turning these armed conflicts into public spectacles. These images’ constant reminder of death and extermination served as a form of social intimidation.

AREA D

THRESHOLD

In 1982, with the death rattle of Argentina’s military dictatorship already audible, the human rights movement demanded the “appearance with life” of the disappeared. At the same time, the poet, essayist and activist Néstor Perlongher wrote his poem Cadavers during a long trip between Buenos Aires and São Paulo, where he had gone into what he himself referred to as a “sexual exile.”

The search for the disappeared provoked reflexion on the various ways in which violence is inscribed on the body. Perlongher’s poem reiterates the phrase “there are cadavers” in order to reveal the existence of dead people everywhere, while language serves as an ideological and sexual insubordination: verbal obscenity is thus linked to sexuality and death.

Pedro Lemebel; his manifesto, “I speak of my difference,” Santiago de Chile, 1986.

Cadavers was published in 1984 in the Buenos Aires literary journal, the Revista de (Poesía), a few months after the fall of the last military junta in Argentina. It was subsequently included in his book Alambres (Wires), from 1987, a volume that positioned itself in favour of critical intervention in the post-dictatorial scene. At the same time that it makes it possible to imagine concentration camps, violence and terror, it contests Argentina’s narrative tradition in the poem’s queering of language.

AREA E

TERRITORIES OF LIBERTY

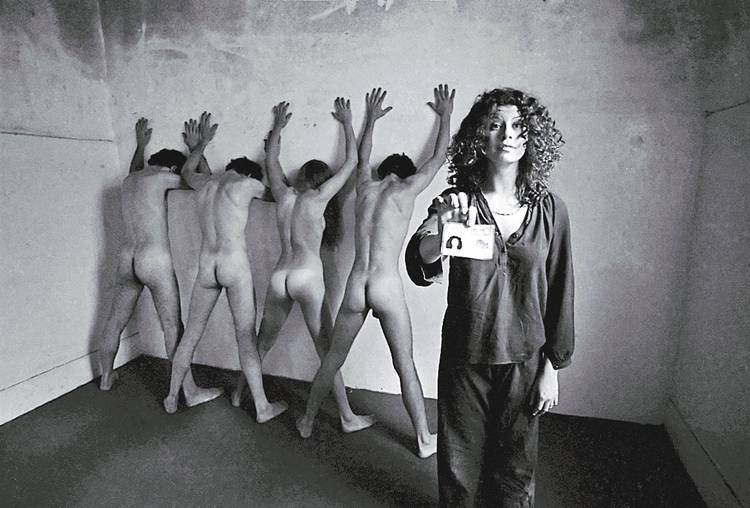

The photographs presented here offer an account of episodes of experimentation with the body in a context full of violence, allowing one to see both the subversive power of bodies and their vulnerability.

Around 1980, the photographer Gianni Mestichelli collaborated with the Compañía Argentina de Mimo (Argentine Mime Company) in the creation of hundreds of fully nude group photographs. The images allude directly to violence and methods of repression: the compositions mimic detentions, firing squads, interrogations and various forms of torture such as the “grill” and the “hood.” Behind mountains of piled bodies, the spectral presence of the disappeared is invoked. The photographs reveal a paradox: alongside the brutal severity of certain images, the links that Mestichelli establishes among the bodies allows for humour and playfulness as well—bodies whose silence speaks eloquently at a time when practically nothing of the sort could be publicly uttered.

In 1984, the Peruvian Sergio Zevallos worked on Suburbios, a series of self-portraits executed in different areas of Lima in collaboration with a street photographer. The artist staged scenes from religious prints in which he fused mystical ecstasy and sexual delirium in the figure of transvestite saints. The contexts he chose for these photographs were run-down areas of the city, full of historical and political connotations, both because of their colonial baroque aesthetic and because of the presence of military forces. In the most ferocious years of Peru’s armed civil conflict, these photographs violently combine the Catholic iconography of martyrdom (religious kitsch) with the images of death recorded on a daily basis by the local press (the kitsch of obscenity), in an allegory of extermination that approaches popular religiosity with iconoclastic irreverence.

AREA F

OVERGOZE

During the Brazilian dictatorship, artists’ and poets’ collectives tested different forms of intervention in the social imaginary with proposals related to the body and sexuality that challenged the castrating austerity imposed by a the State.

In the early eighties, a graffiti-poem comprising a single word, OV3RGOZE (or OVERGOZ3), appeared ubiquitously on the streets of Rio de Janeiro. Created by the Brazilian collective Gang, the text can be translated as the imperative, “over-enjoy” or “beyond-enjoy,” with the full connotations of the verb gozar (evoking pleasure generally, but also specifically orgasm, like the French jouissance). It was a new form of contestation, through parody, humour and the call to pleasure in the public sphere. It was a response to the climate of moral repression, at the same time that it served as a testimony of various communities that promoted sexual liberation before the AIDS crisis.

With this word displayed in the public space, Gang produced a gesture of micro-politics. It served as a call to challenge imposed behavioural norms that were increasingly asphyxiating and castrating, and it revealed a new sensibility that attempted to process oppression and terror through excess, through the carnivalesque, and through disconcerting laughter.

AREA G

PERMANENT DELIRIUM

In the late seventies and early eighties in Argentina and Brazil, three collectives emerged that proposed the reinvention of life through the creative act.

These three groups—the Taller de Investigaciones Teatrales (Theatrical Research Workshop) in Buenos Aires, the Grupo de Arte Experimental Cucaño (Cucaño Experimental Art Group) in Rosario, and Viajou sem Passaporte (Travelled without a Passport), in São Paulo—presented their projects by distancing themselves from Socialist Realism and pamphlet art, which were aesthetically associated with both the Communist Party and Peronist populism in Argentina. Instead, they sought to stimulate the imagination, cause provocation and instigate collective creativity as activities capable of transforming the “normal” conditions of life.

In that climate of isolation and disinformation, they constructed their projects as a vindication of the first Surrealism and its intersection with Trotskyism—a defence of revolutionary art and the creation of a new international Surrealist movement, precisely when military repression had suffocated liberation movements or revolutionary militancy, or made them go clandestine.

A key moment in the construction of this “Trosko-Surrealist Cabinet” is the joint appearance of the three groups in the second Alterarte festival, held in São Paulo in August of 1981. There they devised an intervention inspired by texts by Artaud on the plague, which led to a public scandal and the arrest and deportation of some of the groups’ members.

AREA H

OFFICE OF (COUNTER) INFORMATION

Communication was conceived in this period as an essential tool in political intervention. The open discussion of the information that circulated, the journalistic questioning of the “where,” the “how,” and the “for whom” led to new messages and images that sought to undermine official discourses. Against the informational agendas of the centres of power, the creation of a counter-agenda was put forward as an alternative.

This consisted of activities that might be called counter-information—that is, activities understood as a way of “using the system to turn it upside down,” a confrontation with the established order that usurped its own tools. The manifold experiments that emerged questioned the notion of truth constructed from the centres of power, encouraged alternative uses of media and technologies, and proposed new forms of organisation and mobilisation. They generated networks for the production of non-official information.

Various movements were organised to speak of everything that was being silenced and to carry out acts of denunciation and solidarity, on occasion in direct contact with political movements. Their means of action took as their point of departure a hierarchical structuring of information, providing a new framework for current events and creating networks that could link projects that were isolated though they shared similar objectives. Many of these acts of denunciation escaped the treatment as mere anecdote or spectacle that sources of official information gave to events, and they frequently took the form of irony or humour, in what René de Obladía dubbed “desperation’s amiable form.”

AREAS I & J

PROFANE LITANIES

Clemente Padín’s performances and the installation, Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis (The Mares of the Apocalypse), served as a way of thinking about political violence and disappearances, appealing to the spectator through “the audible body”—the voice—and the insistence on names and numbers.

The bureaucratic recording of proper names, identity numbers and statistics is associated with the State’s policies of documentation and control. This information was used to identify and persecute those individuals who were considered a threat to the established order The subversion of that logic of control in the context of dictatorships served to call upon the State as being responsible for each of those absent bodies.

The sound of the voice thus gives shape to a litany that, by pronouncing the complete names and their identification numbers, corrupts the State’s instrument of control and confronts it with a demand for justice.

AREA K

ARETE

The Guasu Arete is a ceremonial practised by the Chiriguano community of Santa Teresita, in the Paraguayan Chaco. It divides the year in two and requires a three-day pause during which the community renews its social contract, reaffirms itself and mediates conflicts. Arete is a Guarani word that can be translated as “festival”; the root ára refers to time, while the nominal suffix -ete evokes something that is true or extraordinary. It is a festivity conceived as an authentic, exceptional period, a parenthesis in the ordinary passage of time.

During this ritual, the Chiriguanos wear the mask of an ancestor or of a mythical animal. The wearer of the mask, however, does not represent the ancestor or animal, for the mask does not cover or hide the wearer’s face but rather reveals the person’s true social face. In this way, the ritual plays with the ideas of absence and presence, with hiding and revealing one’s individual or social identity, with being and not being. When the ritual concludes, the mask is left behind where the Chiriguanos bury their loved ones when they “depart,” for death is viewed as a voyage to a mythical place of origin.

In the 1980s, Ticio Escobar proposed an anthropological and aesthetic reading of the ritual, which he illustrated with a series of photographs in his book, El mito del arte y el mito del pueblo (The Myth of Art and the Myth of the People, 1986). Escobar draws attention to the invisibility that weighs down upon indigenous peoples and their art, a situation that impedes the indigenous person’s ability to obtain the rights of a fully constituted subject in a country—and a continent—that makes him or her a phantasmagoric figure.

AREA M

ABOLISHING THE PRISON

Several interventions in prisons were carried out with the general objective of reflecting on the notions of liberty, guilt and criminality. Through the prisoners’ participation in acts of poetic and political experimentation, the aim was to manifest the mechanisms of creating economic insecurity and exclusion that were associated in the eighties with the expansion of Neoliberal ideas.

Los Ánjeles Negros (The Black Anjels) have tackled the notion of the criminal in their projects. Puta o Santa (Whore or Saint) was an installation set up on the outer wall of a women’s prison in Santiago, Chile, composed of sixteen modules fashioned from different materials that formed the image of a girl at her first communion with the inscription, “whore or saint.” The intervention, intentionally ephemeral, concluded when the guards pulled the image down from the wall. Through their act of “visual delinquency,” the group utilised dark humour to question the conservative discourse on women’s destinies, making their action coincide with celebrations for International Women’s Day being held a few blocks away from the prison. In another intervention in 1989, Diez puntos tiene tu herida (Your Wound Has Ten Stitches), the group used elements characteristic of agitprop—the screen print poster and the photocopied manifesto—to publicly identify places where drugs and sex were trafficked, thus bringing together the points (or “stitches”—the word is the same in Spanish) that delimit a “dark zone” of the city.

Meanwhile, the Colombian group Mapa Teatro (Theatre Map) presented in Horacio (1993) a theatrical experiment in which eight prisoners from La Picota jail in Bogotá participated as actors. It raised various general issues around the theme of criminals’ humanity.

AREA N/Ñ

SEXUAL DISOBEDIENCE

Beginning in the mid-seventies, in tandem with growing public assertiveness on the part of sexual minorities, a series of artistic projects utilised the sexualised body as a tool of poetic and political action. These practices sought to subvert the identification that heteronormativity establishes between biological sex and gender roles, at the same time that they proposed new models of dissidence. The body and sexuality constitute a privileged territory of production and control and of the inscription of social norms, but they are simultaneously seen as elements of critical resistance.

These instances of “sexual disobedience” exhibit abject, transvestite bodies or bodies subject to technologies of sexual-political correctness. Such bodies alter the taxonomy that distinguishes the “normal” and the “deviant,” and they are open to forms of desire and sexuality that disrupt the masculine/feminine binary.

These practices also confront the division between public and private. Their aim is to call attention to the arbitrariness of the separation between those realms and to the fact that confining sexuality to the private sphere conceals a form of political control of the body. They attack heteronormativity as a political regime through carnivalesque performative practices that celebrate the transformation of the body, that play a kind of baroque transvestism and the transgression of a religious imaginary, or that signal points of commonality for those who practise other forms of sexuality.

AREA X

ANARKY

In the early eighties, in marginal spaces in cities like Buenos Aires, Bahía Blanca, Lima, Santiago de Chile, Mexico City, and São Paulo, a series of lively, self-managed scenes emerged that promoted the establishment of alternative modes of creation, the exchange of ideas and debate. Situated on the fringes of the ideological demands of the traditional Left, they served to expand the field of political action. They were diametrically opposed to official culture and the commercial networks of the art world, through a mixture of poetry, amateur music, participatory architecture, graphic action, transvestism, cabaret, and independent theatre.

In this scene, experimentation with one’s own body through sexual liberation, violence, and drugs was promoted, and strident humour and sordid imagery were used as arms for agitation and as instruments in the search for alternative ways of life, far-removed from authoritarian systems.

Around the notion of “do-it-yourself,” different modes of production and distribution arose, new initiatives were promoted, and the construction of spaces in which each individual could act as a protagonist was encouraged: One can make music without being a “musician”; one can create without being an “artist.” In this way, small recording labels, fanzines, social centres and houses occupied by squatters provided loci for this explosion of aesthetic and political production, on the margins of the culture industry and orthodox militancy, and as a challenge to the traditional separation between artist and audience. The creative social encounter functioned thus as a kind of “strategy of joy” that attempted to raise the collective spirits and to regenerate the social ties broken by terror.

AREA O

ARCHIVES IN USE

This reference space has been conceived as a synthesis of the exhibition and an opportunity to delve further into some of the episodes that comprise it, to which other cases for consideration have been added. It is a dynamic space for further reflexion, based on documents and works, and it is divided into four parts.

The first two parts provide access to the results of the project, “Archives in Use,” carried out by two teams from the Red Conceptualismos del Sur (the “Conceptualisms of the South” Network). The first of these presents a digital archive that brings together hundreds of photographs and documents related to the creative practices developed by the human rights movement in Argentina beginning in the early years of the dictatorship. The second presents the documents produced by the Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA, or Art Actions Collective) in Chile between 1979 and 1985.

The third and fourth parts present, respectively, an extensive video by Glexis Novoa on the history of performance in Cuba in the 1980s and a reference table with a collection of comic books, magazines and underground fanzines from Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Chile, along with other materials from the period.

Finally, there is a diagram which serves as an informational guide or visual synthesis of the exhibition. It shows the relationships of “contamination” and “affinity” among groups, artists and various episodes, revealing their creative, affective and political ties.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| GianniMestichelli.jpg | 51.89 KB |

| GianniMestichelli.jpg | 51.89 KB |

| PedroLemebel.jpg | 46.42 KB |

| DanielGarcia1983.jpg | 99.79 KB |