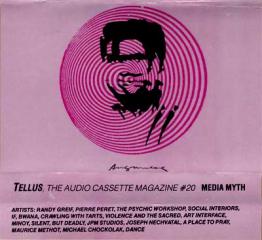

Tellus 20 Media Myth

Tellus 20 Media Myth Tellus 20 :: Media Myth 2

Tellus 20 :: Media Myth 2

Tellus #20 Media Myth has been web published as mp3s at http://www.ubu.com/sound/tellus_20.html

Curated by Joseph Nechvatal

Cover art by Steve Parrino

Total time: 64:38

First published on cassette tape in 1988 by Tellus

01 Randy Greif ‘The Rift In The Earth’ (8:15)

02 Pierre Perret ‘Gaïa, La Terre (excerpt)’ (3:45)

03 The Psychic Workshop ‘Apocalypse from Transmissions of Decadence’ (2:26)

04 Social Interiors ‘Russian Around’ (2:32)

05 If, Bwana ‘The Sound Of…’ (2:55)

06 Crawling With Tarts ‘Plowing And Tilling’ (5:21)

07 Violence and The Sacred ‘Teddy Bear Stinks Real Bad Now (Excerpt)’ (2:47)

08 Art Interface ‘Music For Fans #1′ (5:17)

09 Minoy ‘Tango’ (5:34)

10 Nicolas Collins ‘Devil’s Music 1 (Excerpt)’ (3:15)

11 Silent, But Deadly ‘What’s New Pussy?’ (3:42)

12 JPM Studios ‘#5′ (2:41)

13 Joseph Nechvatal ‘Psychedelic Hermeneutic’ (1:37)

14 A Place To Pray ‘Thelema (excerpt)’ (5:13)

15 Maurice Methot ‘Overture From La Dolarosa’ (2:08)

16 Michael Chockolak ‘Skomorokhi’ (2:59)

17 Dance ‘Nagasaki’ (4:20)

http://continuo.wordpress.com/ writes:

After he curated 'Power Electronics' (Tellus #13) back in 1986, Joseph Nechvatal was back 2 years later with a more ear-friendly but no less challenging compilation tape in the Tellus series. A founding member of Tellus he also contributed artwork to issue #4 and, as a composer, appeared several times on various Tellus issues. 'Media Myth' is devoted to composers using mass-media quotations and audio-samples, and favoring sound-surgery as a composing method, that is: sampling, collage or concrete music.

The Michael Chockolak track (actually 'Chocholak') is a beautiful sampler lullaby using ethnic chant as source material, a bit like a slowed-down version of Roberto Musci & Giovanni Venosta. There's another beautiful electronic instrumental melody by Californian Minoy, a kind of valse. Several composers like Art Interface, Crawling With Tarts or Pierre Perret choose soothing sounds to achieve their de-construction of our sonic environment, the latter delivering his personal take on concrete music out of field-recordings. Weather concrete music is collage music or social commentary is open to discussion, though. More often than not on this tape, composers will unceremoniously sample from pop songs, famous operas, preachermen, porn material or public announcements (Maurice Methot, A Place To Pray (Rune Brøndbo and Olav Hagen from Germany). I assume the goal is to put everything into perspective, to create ironical conflagrations of nonsensical sound bits - especially in the Silent, But Deadly track, a risqué play on 'What's New Pussycat'. The name of the band says it all, I guess. The band included the famous NY dj Special Ed, worth checking out on WFMU. The Nicolas Collins' sound concatenation is even more cruel, where the needle-like precision samples are so short as to erase any meaning the sound excerpts might have for the listener, and you're left with pure meaningless aural stimulus - arguably what the composer think of mass media muzzak. Canadian collective Violence And The Sacred use Maoist-era chinese samples to good effect, in a juxtaposition with media idle chatter. Aussies Social Interior achieve similar surreal effects with russian language - the most exhilarating track on Tellus #20. It seems participants consider language as something to de-construct, to reduce to bits, to pulverize anyhow.

Tellus 20 :: Media Myth 2

Tellus 20 :: Media Myth 2

On his blog post.thing.net, Joseph Nechvatal posted this article called 'Towards a Sound Ecstatic Electronica', written 2000, including theoretical afterthoughts on the two Tellus cassettes he curated. He starts with describing the political and moral context of the Reagan era (1981-89), the so-called 'Reaganomics'. A time of media hysteria and massive information overload where huge amounts of phantasmagorical data are flooding from every possible medium. At the heart of his theory is the assumption that artists politically react to this media overload with 'anti-social phantasmagoria', at best ultimately reducing the information to its bare 'nerve energy'. Nechvatal assume electronic technology can be an antithesis to the controlling technical world. It is thus the electronic composer's responsibility to be aware of his environment and to make us conscious of its wickedness. We're talking here about the 1986-88 period, while Reagan was still in charge. This was also the time when Lloyd Dunn's Photostatic Magazine (1983-93) was published in Iowa, advocating xerography as a political graphic weapon ; supreme ironist Negativland released their 'Escape from Noise' LP in California in 1987 ; John Oswald released his Plunderphonics' EP in 1988. So this was definitely a time for cultural terrorism in the US. Nechvatal's writing is infused with french theory. We find echoes from Baudrillard's excess of signs theory and the copy-replacing-the-original motto. Jacques Attali's 'Noise' (translated in the US in 1985) comes to mind as well, where he considers music as a mere industrial sector but still pop music as a strain of subversion. These ambitious post-structuralist references enhance the impact of the 2 cassettes Joseph Nechvatal curated (Tellus #13 & 20), and I have yet to read a more challenging piece of writing on humble cassette releases.

May I conjecture, though, the 1980s material abundance served to hide the increasing formidable US debt under Reagan. Might one then not ask what the accordingly excessive information overload of the 1980s served to hide? I think this would be a valid question, and the answer might come as an inflatable hollow structure holding nothing but its own lack of substance - this is the Myth from the cassette title, after all, and myths are created by artists. Jacques Attali again: 'Music runs parallel to human society, is structured like it, and changes when it does.' The media frenzy opening on total intellectual void, I suspect addressing the media overload is like addressing a mirage. My point is this: the artists on 'Media Myth' were more taking part in the media overload than reacting against it. Just because you use a sampler doesn't make a cultural theorist out of you, at least not much more than the use of a banjo. But admittedly on 'Media Myth', unlike the media dumkopfs they vilipended, composers delivered exciting and engaging music.

Towards a Sound Ecstatic Electronica: on Tellus 20

Here are my notes which are referred to above from 2000 on Tellus project 20 and 13

Towards a Sound Ecstatic Electronica : the Rational Behind Tellus Issues “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”

by

Joseph Nechvatal

To begin; the basic premise behind “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth” was the exploration of the introspective world of the ear under the influence of the era’s high-frequency electronic environment. Since it was difficult making sense of the 1980’s swirling media society, the general proposition behind “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth” was to look for a paradoxical summation of this uncertainty by looking for artists who took advantage of the time’s superficial saturation; a saturation so dense that it failed to communicate anything particular at all upon which we could concur - except perhaps its overall incomprehensible sense of ripe delirium - as the Reaganomic reproduction system pulsed with higher and higher, faster and faster, flows of senseless info-data to the point of near hysteria.

Perhaps the result of this ripe information abundance was that the greater the amount of Reaganomic information that flowed, the greater the incredulity which it produced; at least for thinking, questioning artists. So, the tremendous load of data produced and reproduced all around us then ultimately seemed to make less, not more, conventional sense. Indeed, this feeling became the premise of both “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”.

This supposition, it now seems to me, plays into the history of abstract art which teaches us that art may refuse to recognize all thought as existing in the form of representation, and that by scanning the spread of representation sound art may formulate an understanding of the laws that provide junk bond representation with its organizational basis. As a result, in my view, it was electronic-based sound art's onus to see what unconventional, paradoxical, summational sense - in terms of the subjective world of the imagination – art might make of the 1980s based on an appropriately decadent reading of the time’s paradoxically material-based (yet electronically activated) media environment.

Such a basically abstract, artistic, paradoxical/summational fancy began with the presumption that an information-loaded nuclear weapon had already exploded, showering us with bits of radioactive-like informational sound bytes - thus drastically changing the way in which we perceive and act, even in our subconscious dream worlds. It is this internal, subconscious, paradoxical drama of the Reaganomic 80s - this subconscious contradictory tension - which I found potentially interesting in conceiving “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth” and as a subject specifically suitable for electronic-based sound art.

Electronic-based sound art, by virtue of its distinctive electron constitution of fluidity, floats in an extensive stratosphere of virtuality. Hence, the particular constitution of “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth” is best seen, perhaps today, as an osmotic membrane: a blotter of the 80s instantaneous ubiquity/proliferation. Consequently, “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth” reflected (and worked with) social power. “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”, when viewed as shaped by the de-centered electronic overload of the 80s, is understood today as a flustered code of digital signifiers, a confused collective representation which bewilderingly mutated the ideology of its own reproduction.

So, the question for “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth” was how could artists symbolically turn these de-centered power codes into artistic abstractions of social merit? Perhaps it was possible because we knew, somewhere, that these symbolic codes - which, after all, helter-skelter, make us up - are positively phantasmagorical.

This is still, of course, true today. Based on the premises of “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”, perhaps then a socially relevant digitally-based audio creativity can be found also in today's electronic-based art's ecstatic potentiality - in that electrons partake (and make up) the all-encompassing phantasmagorical/technological sign-field within which we live and which defines us (at least in part). Since prevailing representation is made up of conventional, rigid social signs (and sound art typically of unconventional irresponsible signs - the mode that represents the real arbitrary nature of all signs as it subverts the socially controlled system of meaning) - electronic-based sound art may offer us the opportunity for the creation of relevant and applicable anti-social phantasmagorical signs (hence abstract ecstatic anti-signs) which may continue to mentally move and multiply us without stop. Yet this fancied aesthetic non-knowledge is certainly the most erudite, the most aware, the most conscious area of our current identity, as it is also the phantasmal depths from which all digital representation emerges in its precarious, but glittering, existence.

Indeed it was this quivering phantasmal cohesion that maintains the sovereign and secret sway over each and every audio sample - this phantasmal vibrating - which I found interesting in conceiving both “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”; a sway beyond reductive minimalist abstraction into an excessive hybrid abstraction. An audio art, which is in theory, opposed to the tabular mental space laid out by classical thought.

If the ultra-dissemination of the sign in electronic-based sound art may create such phantasmagorical hyper-logics of use to the formation of art, “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”’s potential may prove useful in questioning received notions of representation when viewed against assumptions of utility versus pleasure. Indeed, perhaps “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”’s unconscious intention was to achieve an ultimate phantasmal integration by dissolving audio form into its original electronic foundation of nerve energy. Such a dynamic sense of aesthetic electronica as nervous contemplative vision might suggest the potential of social re-configuration then as it subsumes our previous world of simulation/representation into a phantasmagorical nexus of over-lapping linked hybrid observations of the outer world with precise extractions of human mentality. Encounters, then, with “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”, one may assume, might create an opportunity for social transgression - and for a vertiginous ecstasy of thought.

Surely such a hybrid electronica/phantasmal impetus can help release pent up ecstatic energies in that the more overwhelming and restrictive the social mechanism, the more exaggerated are the resulting effects - and hence excel the assumed determinism of the technological-based phenomenon inherent (supposedly) in our post-industrial information society. Therefore, this way, “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth” may serve as an ecstatic impulse/phenomena which prolif-erates in proportion to the technicization of society - as such a nervous electronica-ecstasy may occur as a result of the technological society's obsession with the phantasmal character of electronic speed-proliferation.

Prediction then for the legacy of “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”: as human psychic energies are stifled and/or bypassed by certain controlling aspects of mass technology, such a nervous ecstatic phenomena will increasingly break out in forms of art. Similarly, simulation technology (when used in the creation of electronica-based art) will promote an indispensable alienation from the socially constructed self necessary for the outburst of such nervously ecstatic experiences/acts. Inversely, electronic technology will enable the contemporary artist to express nervous ecstatic reactions in ways never before possible. Thus this nervous ecstatic counteraction will provide a phantasmal defiance through transport aimed against the controlling world's blandness and self-destructiveness. This aesthetic philosophy will provide a fundamental antithesis to the authoritarian, mechanical, simulated rigidities of the controlling technical world.

May I just say that the nervous phantasmal play found in “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth” has the most urgent political/social ramifications in our media saturated society today. The artists’, I think, well-founded but ambiguous phantasmal model for sound art indicates the capacity for the electronic media's worth as it provides the explication of the nervous phantasmal links that abet communications. Hence, excessive audio abstractions, such as those found in “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth”, can be, in a sense, the representation of all representation when they attempt to represent the unlimited field of representation, which non-utilitarian phantasmal ideology attempts to scrutinize in accordance with a non-discursive method which now appears as an abstract digital metaphysics; a nerve-based metaphysics which excessive abstraction helps to step outside of itself to posit itself outside of the mechanics of uniform dogmatism.

The emergence of the spectral audio project I have outlined in “Power Electronics” and “Media Myth” will, I hope, contribute to an inventing a nervous sound art in which what matters is no longer sound identities, or audio logos, but rather dense, phantasmagorical forces developed on the basis of inclusion - where from now on things will be heard only from the depths of this nervous inclusive density - withdrawn into itself, perhaps - adumbrated and darkened by its obscurity - but bound tightly together and inescapably grouped by the vigor that is hidden in a depth that is fermenting a phantasmagorical aural discourse which is both nervously capricious and, paradoxically, socially responsible.

Joseph Nechvatal

6/6/2000 Paris