The Summer of Love show at the Whitney Museum is great fun. It’s full of experiences – walk-in and peer-in rooms and boxes, kinetic sculptures, video and film, album and underground newspaper covers, photos of celebs and jes folks, and even some painting and sculpture. Coming from the Tate Liverpool, the show’s strategy is to represent visual culture rather than high art. That’s cool. You can almost hear the music and taste the drugs…

I was struck by the Jud Yalkut film “Yayoi Kusama, Self-Obliteration.” (A clip from this film is linked out of a 1999 Bomb interview with Kusama -- http://www.bombsite.com/archive/kusama/kusama1.html#videoDots1). The extremely prolific Japanese artist who has become a perennial at Robert Miller’s Chelsea gallery made a dramatic impact in 1960s New York. The tabloids and underground press alike loved her work with public nude Happenings and her sex-based churchish rituals. Now permanently institutionalized, Kusama is a poster child for the mid-century ideal of creative madness.

Yalkut filmed the artist painting her signature dots onto a canvas floating in a pond. As the canvas starts to sink, Kusama continues to paint, and her colors float in the water. The image was a metaphor for the show and the period – free floating color, color in suspension, even color where it doesn’t belong. In another scene in the film, Kusama’s body-painted initiates simulate fucking. (This accounts for one of many museum content warning signs in the show: seeing is dangerous.) Painted up as they are, the film's subjects are clearly fucking to be seen, which may not entirely be the case in such orgy-classics as Jack Smith's “Flaming Creatures” and Carolee Schneeman's “Meat Joy.” Kusama's fashion, body painting, and ritual performance modalities organized some of the period’s most picturesque collective events.

With artists’ collectives become a favorite flavor in today’s international exhibitions, it is instructive to see them presented as they were then, operating in the midst of broad-based cultural and political movements.

The collectively produced visual culture of this moment was unfolding in the context of experiments with art and technology, many of them produced to accompany music concerts. The Joshua Light Show is featured, as it was in the ’05 Visual Music exhibition at the Hirshhorn Museum (http://www.hirshhorn.si.edu/visualmusic/lightshows.html). (The Joshua’s former director became a successful television producer and a kingpin in the fabled albeit short-lived internet venture Pseudo.com.) Light show films and relics in Summer of Love are shown with machines by the USCO concrete poets’ collective and light organs by forgotten artists. These amazing machines are lying hidden in museum basements since the interest in kinetic art collapsed in the 1970s.

When a museum show makes crowds happy with art, it seems ill-natured to carp at it. But, as the influential ‘60s cartoonist snarls from the cover of his recently published R. Crumb Handbook, “I’m not here to be polite!”

This show is an import. Like Jimi Hendrix. It is continuously dispiriting to see New York culture validated and fed back to the city by out-of-towners. (It’s the cosmopolitan as hayseed: “You mean you like it? Well, gawrsh!”) The Londoners will always miss stuff. Just fr'instance, Don Snyder's remarkable photographs (gathered in his book Aquarian Odyssey), the graphic design collective Group Image on the Lower East Side, Ed Sanders’ Fuck You magazine of the arts, kinetic art curator Willoughby Sharp's service as art commissar to the Yippie movement. From the west, we're missing the mostly-California based national commune journal Kaliflower (see some of those images at http://www.diggers.org/kaliflower/volume_1.htm).

All these absences point to a seemingly permanent structural defect in museum curatorial procedures. The Whitney has opened itself up to a visual culture approach, mixing the high art and the artisanal. Yet they have not changed their methods, which exist not to organize knowledge but to consecrate art market value. This London package deal does not serve to organize a local New York psychedelic history, which, as the show itself demonstrates, is very substantially underknown. Can it be that a museum of American art cannot bring itself to trust its local artists in presenting a show like this?

A companion show of photographs and video works upstairs is called Resistance. This profoundly forgettable little assemblage is conditioned by a video with a dirge-like soundtrack (unlike the show downstairs, which is surprisingly quiet). The notion of revolutionary joy apparently has not occurred to contemporary artists and curators who are here seen to be endlessly massaging martyrs' wounds. If it weren’t clearly crocodile tears, this curation could be a wake for the failed American Leninist revolution. The missing Rosa Luxembourg here is Abbie Hoffman. His “revolution for the hell of it!” is not sad. It’s trippy. Art historian David Joselit recently compared Abbie to Warhol, and the soft-pedalling of his presence (and absence in Resistance) speaks to a primal fear of his message. He’s worse than queer, he’s a mass media revolutionary.

The new book edited by Clayton Patterson, et al., Resistance: A Radical Social and Political History of the Lower East Side contains many stories of the rich texture of just that here. What did this resistance look like? We still don't know enough. I was a co-editor on Resistance, and learned of the Motherfuckers' broadsides and antic actions, and the women's issues of the underground newspaper Rat (discussed in Allan Antliff's new book Anarchy and Art).

The Summer of Love has been disconnected from its political effects and intentions. Big surprise. There's a lot more work to be done here to bring this history back out of control, where it belongs.

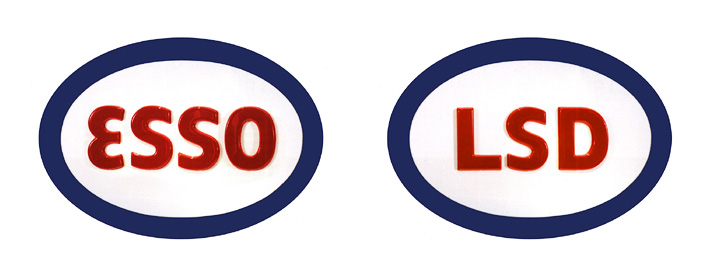

PHOTO CAP:

Oyvind Fahlstrom, ESSO-LSD, 1967

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 07_esso_lsd_large.jpg | 44.8 KB |

Living in the Eyes Age

>bring this history back out of control where it belongs.

Hardly a simple matter of recontextualization. Sub-culture lives drowning underwater nostrils flaring just below see level. By the sounds of it this show just cans the tuna for public consumption so what. It's an intro to contemporary preservation. Let them eat flake.